National Geographic Documentary: Area 51 Declassified (full episode 45minutes)

Video Link...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JByUxV1X_pg

I Watched this Video and Really Enjoyed it. The Stories are told by men who actually worked at "Area 51", back in the "Cold War" Days. There's some more info from some Research that I did after watching the Video, Below...

Don

Lockheed A-12

| A-12 | |

|---|---|

| An A-12 aircraft (serial number 06932) | |

| Role | High-altitude reconnaissance aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Corporation |

| First flight | 26 April 1962 |

| Introduction | 1967 |

| Retired | 1968 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary user | Central Intelligence Agency |

| Number built | A-12: 13; M-21: 2 |

| Variants | Lockheed YF-12 |

| Developed into | Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird |

The Lockheed A-12 was a reconnaissance aircraft built for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) by Lockheed's famed Skunk Works, based on the designs of Clarence "Kelly" Johnson. The A-12 was produced from 1962 to 1964, and was in operation from 1963 until 1968. The single-seat design, which first flew in April 1962, was the precursor to both the twin-seat U.S. Air Force YF-12 prototype interceptor and the famous SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance aircraft. The aircraft's final mission was flown in May 1968, and the program and aircraft retired in June of that year. Officially secret for over forty years, the CIA began declassifying A-12 program details for release in 2007.[1]

Contents |

Design and development

With the failure of the CIA's Project Rainbow to reduce the radar cross section of the U-2, preliminary work began inside Lockheed in late 1957 to develop a follow-on aircraft to overfly the Soviet Union. Under Project Gusto the designs were nicknamed "Archangel", after the U-2 program, which had been known as "Angel". As the aircraft designs evolved and configuration changes occurred, the internal Lockheed designation changed from Archangel-1 to Archangel-2, and so on. These nicknames for the evolving designs soon simply became known as "A-1", "A-2", etc.[2]

These designs had reached the A-11 stage when the program was reviewed. The A-11 was competing against a Convair proposal called Kingfish, of roughly similar performance. However, the Kingfish included a number of features that greatly reduced its radar cross section, which was seen as favorable to the board. Lockheed responded with a simple update of the A-11, adding twin canted fins instead of a single right-angle one, and adding a number of areas of non-metallic materials. This became the A-12 design. On 26 January 1960, the CIA ordered 12 A-12 aircraft.[citation needed] After selection by the CIA, further design and production of the A-12 took place under the code-name Oxcart.

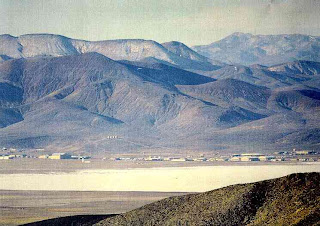

After development and production at the Skunk Works, in Burbank, California, the first A-12 was transferred to Groom Lake test facility,[3] where on 26 April 1962, Lockheed test pilot Lou Schalk took the A-12 on its shakedown flight. Many internal documents and references to individual aircraft used Johnson's preferred designation, using the prefix, "the Article" for the specific examples. Thus on the A-12's first flight, the subject aircraft was identified as "Article 121". The first official flight occurred on 30 April.[4] On its first supersonic flight, in early May 1962, the A-12 reached speeds of Mach 1.1.[citation needed]

The first five A-12s, in 1962, were initially flown with Pratt & Whitney J75 engines capable of 17,000 lbf (76 kN) thrust each, enabling the J75-equipped A-12s to obtain speeds of approximately Mach 2.0. On 5 October 1962, with the newly developed J58 engines, the A-12 flew with one J75 engine, and one J58 engine. By early 1963, the A-12 was flying with J58 engines, and during 1963 these J58-equipped A-12s obtained speeds of Mach 3.2. Also, in 1963, the program experienced its first loss when, on 24 May, "Article 123"[5] piloted by Kenneth S. Collins crashed near Wendover, Utah.[citation needed]

The reaction to the crash illustrated the secrecy over, and importance of, the project. The CIA called the aircraft an F-105 as a cover story;[6] local law enforcement and a passing family were warned with "dire consequences" to keep quiet about the crash.[5] Each was also paid $25,000 in cash ($189,783 today[7]) to do so; the project often used such cash payments to avoid outside enquiries into its operations.[5] The project received ample funding; contracted security guards were paid $1,000 monthly ($7,591 today[7]) with free housing on base, and chefs from Las Vegas were available 24 hours a day for steak, Maine lobster, or other requests.[5]

In June 1964, the last A-12 was delivered to Groom Lake,[8] from where the fleet made a total of 2,850 test flights.[6] A total of 18 aircraft were built through the program's production run. Of these, 13 were A-12s, three were prototype YF-12A interceptors for the U.S. Air Force (not funded under the OXCART program), and two were M-21 reconnaissance drone carriers. One of the 13 A-12s was a dedicated trainer aircraft with a second seat, located behind the pilot and raised to permit the Instructor Pilot to see forward. The A-12 trainer "Titanium Goose", retained the J75 powerplants for its entire service life.[9]

Operational history

Although originally designed to succeed the U-2 in overflights over the Soviet Union and Cuba, the A-12 was never used for either role. After a U-2 was shot down in May 1960, the Soviet Union was considered too dangerous to overfly except in an emergency (and overflights were no longer necessary[10] due to reconnaissance satellites) and, although crews trained for the role of flying over Cuba, U-2s continued to be adequate there.[11]

The Director of the C.I.A. decided to deploy some A-12s to Asia. The first A-12 arrived at Kadena Air Base on Okinawa on 22 May 1967. With the arrival of two more planes (on 24 May, and 27 May) this unit was declared to be operational on 30 May, and it began Operation Black Shield on 31 May.[12] Mel Vojvodich flew the first Black Shield operation, over North Vietnam, photographing surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites, flying at 80,000 ft (24,000 m), and at about Mach 3.1. During 1967 from the Kadena Air Base, the A-12s carried out 22 sorties in support of the War in Vietnam. Then during 1968, Black Shield conducted operations in Vietnam and it also carried out sorties during the Pueblo Crisis with North Korea.

During its deployment on Okinawa, the A-12s (and later the SR-71) and by extension their pilots, were nicknamed Habu after a cobra-like Okinawan pit viper that the local people thought the plane resembled.[citation needed]

Retirement

The A-12 program was ended on 28 December 1966[13] — even before Black Shield began in 1967 — due to budget concerns[14] and because of the forthcoming twin-seated SR-71 that began to arrive at Kadena during March 1968.

Ronald L. Layton flew the 29th and final A-12 mission on 8 May 1968, over North Korea. On 4 June 1968, just 2½ weeks before the retirement of the entire A-12 fleet, an A-12 out of Kadena, piloted by Jack Weeks, was lost over the Pacific Ocean near the Philippines while conducting a functional check flight after the replacement of one of its engines.[14][15] Francis J. Murray took the final A-12 flight on 21 June 1968, to Palmdale, California.[citation needed]

On 26 June 1968, Vice Admiral Rufus L. Taylor, the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, presented the CIA Intelligence Star for valor to Weeks' widow and pilots Collins, Layton, Murray, Vojvodich, and Dennis B. Sullivan for participation in Black Shield.[14][16][17]

The deployed A-12s and the eight non-deployed aircraft were placed in storage at Palmdale. All surviving aircraft remained there for nearly 20 years before being sent to museums around the United States. On 20 January 2007, despite protests by Minnesota's legislature and volunteers who had maintained it in display condition, the A-12 preserved in Minneapolis, Minnesota, was dismantled to ship to CIA Headquarters to be displayed there.[18]

Timeline

The following timeline describes the overlap of the development and operation of the A-12, and the evolution of its successor, the SR-71.

- 16 August 1956: Following Soviet protest of U-2 overflights, Richard M. Bissell, Jr. conducts the first meeting on reducing the radar cross section of the U-2. This evolves into Project Rainbow.

- December 1957: Lockheed begins designing subsonic stealthy aircraft under what will become Project Gusto.

- 24 December 1957: First J-58 engine run.

- 21 April 1958: Kelly Johnson makes first notes on a Mach 3 aircraft, initially called the U-3, but eventually evolving into Archangel I.

- November 1958: The Land panel provisionally selects Convair Fish (B-58-launched parasite) over Lockheed's A-3.

- June 1959: The Land panel provisionally selects Lockheed A-11 over Convair Fish. Both companies instructed to re-design their aircraft.

- 14 September 1959: CIA awards antiradar study, aerodynamic structural tests, and engineering designs, selecting Lockheed's A-12 over rival Convair's Kingfish. Project Oxcart established.

- 26 January 1960: CIA orders 12 A-12 aircraft.

- 1 May 1960: Francis Gary Powers is shot down in a U-2 over the Soviet Union.

- 26 April 1962: First flight of A-12 with Lockheed test pilot Louis Schalk at Groom Lake.

- 13 June 1962: SR-71 mock-up reviewed by USAF.

- 30 July 1962: J58 engine completes pre-flight testing.

- October 1962: A-12s first flown with J58 engines

- 28 December 1962: Lockheed signs contract to build six SR-71 aircraft.

- January 1963: A-12 fleet operating with J58 engines

- 24 May 1963: Loss of first A-12 (#60–6926)

- 20 July 1963: First mach 3 flight

- 7 August 1963: First flight of the YF-12A with Lockheed test pilot James Eastham at Groom Lake.

- June 1964: Last production A-12 delivered to Groom Lake.

- 25 July 1964: President Johnson makes public announcement of SR-71.

- 29 October 1964: SR-71 prototype (#61-7950) delivered to Palmdale.

- 22 December 1964: First flight of the SR-71 with Lockheed test pilot Bob Gilliland at AF Plant #42. First mated flight of the MD-21 with Lockheed test pilot Bill Park at Groom Lake.

- 28 December 1966: Decision to terminate A-12 program by June 1968.

- 31 May 1967: A-12s conduct Black Shield operations out of Kadena

- 3 November 1967: A-12 and SR-71 conduct a reconnaissance fly-off. Results were questionable.

- 26 January 1968: North Korea A-12 overflight by Jack Weeks photo-locates the captured USS Pueblo in Changjahwan Bay harbor.[19]

- 5 February 1968: Lockheed ordered to destroy A-12, YF-12 and SR-71 tooling.

- 8 March 1968: First SR-71A (#61-7978) arrives at Kadena AB (OL 8) to replace A-12s.

- 21 March 1968: First SR-71 (#61-7976) operational mission flown from Kadena AB over Vietnam.

- 8 May 1968: Jack Layton flies last operational A-12 sortie, over North Korea.

- 5 June 1968: Loss of last A-12 (#60–6932)

- 21 June 1968: Final A-12 flight to Palmdale, California.

For the continuation of the Oxcart timeline, covering the duration of operational life for the SR-71, see SR-71 timeline.

Variants

Training variant

The A-12 training variant (60-692 "Titanium Goose") was a two-seat model with two cockpits in tandem with the rear cockpit raised and slightly offset. In case of emergency, the trainer was designed to allow the flight instructor to take control. Other than the modifications required to accommodate the dual controls and new cockpit configuration, the trainer was very similar to A-12 in terms of appearance and performance.[citation needed]

YF-12A

The YF-12 program was a limited production variant of the A-12. Lockheed convinced the U.S. Air Force that an aircraft based on the A-12 would provide a less costly alternative to the recently canceled North American Aviation XF-108, since much of the design and development work on the YF-12 had already been done and paid for. Thus, in 1960 the Air Force agreed to take the seventh through ninth slots on the A-12 production line and have them completed in the YF-12A interceptor configuration.[20]

The main changes involved modifying the aircraft's nose to accommodate the Hughes AN/ASG-18 fire-control radar originally developed for the XF-108, and the addition of a second cockpit for a crew member to operate the fire control radar. The nose modifications changed the aircraft's aerodynamics enough to require ventral fins to be mounted under the fuselage and engine nacelles to maintain stability. Finally, bays previously used to house the A-12's reconnaissance equipment were converted to carry missiles.[citation needed]

M-21

One notable variant of the basic A-12 design was the M-21, used to carry and launch the Lockheed D-21, an unmanned, faster and higher-flying reconnaissance drone. The M-21 was a modified version of the A-12 with a second cockpit for a Launch Control Operator/Officer (LCO) in the place of the A-12's Q bay; the M-21 also included a pylon on its back for mounting the drone.[21] The D-21 was completely autonomous; after being launched it would overfly the target, travel to a predetermined rendezvous point and eject its data package. The package would be recovered in midair by a C-130 Hercules and the drone would self-destruct.[22]

The program to develop this system was canceled in 1966 after a drone collided with the mother ship at launch, destroying the M-21. The crew survived the midair collision but the LCO drowned when he landed in the ocean and his flight suit filled with water.[23] The modified D-21B drone was carried on a pylon under the wing of the B-52 bomber. The drone performed operational missions over China from 1969 to 1971.[24]

A-12 aircraft production and disposition

| Serial number | Model | Location or fate |

|---|---|---|

| 60-6924 | A-12 | Air Force Flight Test Center Museum Annex, Blackbird Airpark, at Plant 42, Palmdale, California. 606924 was the first A-12 to fly. |

| 60-6925 | A-12 | Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum, parked on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid, New York City |

| 60-6926 | A-12 | Lost, 24 May 1963 |

| 60-6927 | A-12 | California Science Center in Los Angeles, California (Two-canopied trainer model, "Titanium Goose") |

| 60-6928 | A-12 | Lost, 5 January 1967 |

| 60-6929 | A-12 | Lost, 28 December 1967 |

| 60-6930 | A-12 | U.S. Space and Rocket Center, Huntsville, Alabama |

| 60-6931 | A-12 | CIA Headquarters, Langley, Virginia[N 1] |

| 60-6932 | A-12 | Lost, 4 June 1968 |

| 60-6933 | A-12 | San Diego Aerospace Museum, Balboa Park, San Diego, California |

| 60-6937 | A-12 | Southern Museum of Flight, Birmingham, Alabama |

| 60-6938 | A-12 | Battleship Memorial Park (USS Alabama), Mobile, Alabama |

| 60-6939 | A-12 | Lost, 9 July 1964 |

| 60-6940 | M-21 | Museum of Flight, Seattle, Washington |

| 60-6941 | M-21 | Lost, 30 July 1966 |

Specifications (A-12)

Data from A-12 Utility Flight Manual,[25] Pace[26]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1 (2 for trainer variant)

- Length: 101.6 ft (30.97 m)

- Wingspan: 55.62 ft (16.95 m)

- Height: 18.45 ft (5.62 m)

- Wing area: 1,795 ft² (170 m²)

- Empty weight: 54,600 lb (24,800 kg)

- Loaded weight: 124,600 lb (56,500 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney J58-1 continuous bleed-afterburning turbojets, 32,500 lbf (144 kN) each

- Payload: 2,500 lb (1,100 kg) of reconnaissance sensors

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 3.35 (2,210 mph, 3,560 km/h) at 75,000 ft (23,000 m)

- Range: 2,200 nmi (2,500 mi, 4,000 km)

- Service ceiling: 95,000 ft (29,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 11,800 ft/min (60 m/s)

- Wing loading: 65 lb/ft² (320 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.56

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

- Notes

- ^ "Article 128", unveiled on Wednesday, 19 September 2007, at CIA Headquarters in Langley, Virgina. On hand was Ken Collins, a retired Air Force Colonel, one of only six pilots to fly the A-12s.

- Citations

- ^ Jacobsen, Annie (5 April 2009). "The Road to Area 51". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ "The U-2's Intended Successor: Project Oxcart 1956–1968". Central Intelligence Agency, approved for release by the CIA in October 1994. Retrieved: 26 January 2007.

- ^ Jacobson 2011, p. 51.

- ^ "A-12 First Flight." Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 13 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d Lacitis, Erik. "Area 51 vets break silence: Sorry, but no space aliens or UFOs." The Seattle Times, 27 March 2010.

- ^ a b Jacobsen, Annie. "The Road to Area 51." Los Angeles Times, 5 April 2009.

- ^ a b Staff. Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2012. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ "SR-71 Blackbird." Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 13 October 2010.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, p. 16.

- ^ McIninch 1996, p. 19.

- ^ McIninch 1996, p. 20.

- ^ McIninch 1996, pp. 25–27.

- ^ McIninch 1996, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Robarge, David. "A Futile Fight for Survival. Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft." U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, Center for the Study of Intelligence, CSI Publications, 27 June 2007. Retrieved: 13 April 2009.

- ^ McIninch 1996, p. 33.

- ^ McIninch 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Hayden, General Michael V. "General Hayden's Remarks at A-12 Presentation Ceremony." Central Intelligence Agency, Remarks of Director of the Central Intelligence Agency at the A-12 Presentation Ceremony, 19 September 2007. Retrieved: 10 April 2009.

- ^ Karp, Jonathan. "Stealthy Maneuver: The CIA Captures An A-12 Blackbird". The Wall Street Journal, A1, 26 January 2007. Retrieved: 10 April 2009.

- ^ Jacobson 2011, p. 273.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Donald 2003, pp. 154–155.

- ^ "MD-21 crash footage." YouTube. Retrieved: 13 October 2010.

- ^ Donald 2003, pp. 155–156.

- ^ "A-12 Utility Flight Manual (Copy 15, Version 15 September 1968)." CIA, 15 June 1968. Retrieved: 5 April 2010.

- ^ Pace 2004, pp. 105, 110.

- Bibliography

- Donald, David, ed. "Lockheed's Blackbirds: A-12, YF-12 and SR-71". Black Jets. Norwalk, Connecticut: AIRtime, 2003. ISBN 1-880588-67-6.

- Jacobson, Annie.Area 51. London: Orion Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1-4091-4113-6.

- Landis, Tony R. and Dennis R. Jenkins. Lockheed Blackbirds. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Specialty Press, revised edition, 2005. ISBN 1-58007-086-8.

- McIninch, Thomas. "The Oxcart Story." Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 2 July 1996. Retrieved: 10 April 2009.

- Pace, Steve. Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird. Swindon, UK: The Crowood Press, 2004. ISBN 1-86126-697-9.

- Additional sources

- Graham, Richard H. SR-71 Revealed: The Inside Story. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 1996. ISBN 978-0-7603-0122-7.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. Lockheed Secret Projects: Inside the Skunk Works. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7603-0914-8.

- Johnson, C.L. Kelly: More Than My Share of it All. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 1985. ISBN 0-87474-491-1.

- Lovick, Edward, Jr. Radar Man: A Personal History of Stealth. Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4502-4802-0.

- Merlin, Peter W. From Archangel to Senior Crown: Design and Development of the Blackbird (Library of Flight Series). Reston, Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), 2008. ISBN 978-1-56347-933-5.

- Pedlow, Gregory W. and Donald E. Welzenbach. The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance: The U-2 and OXCART Programs, 1954–1974. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 1992. ISBN 0-7881-8326-5.

- Rich, Ben R. and Leo Janos. Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My years at Lockheed. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1994. ISBN 0-316-7433.

- Shul, Brian and Sheila Kathleen O'Grady. Sled Driver: Flying the World's Fastest Jet. Marysville, California: Gallery One, 1994. ISBN 0-929823-08-7.

- Suhler, Paul A. From RAINBOW to GUSTO: Stealth and the Design of the Lockheed Blackbird (Library of Flight Series). Reston, Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), 2009. ISBN 978-1-60086-712-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Lockheed A-12 |

- Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft by David Robarge. (Cia.gov)

- FOIA documents on OXCART (Declassified 21 January 2008)

- "Sheep Dipping" Conversion of Air Force Officers to CIA For Project Oxcart

- A-12 page on RoadRunners Internationale site

- A-12T Exhibit at California Science Center

- Differences between the A-12 and SR-71

- Blackbird Spotting maps the location of every existing Blackbird, with aerial photos from Google Maps

- Photographs and disposition of the "Habu" aircraft at habu.org

- The U-2's Intended Successor: Project Oxcart (Chapter 6 of "The CIA and Overhead Reconnaissance", by Pedlow & Welzenbach)

- USAF Aircraft Serial Numbers for 1960, including all A-12s, YF-12As and M-21s

- "The Real X-Jet", Air & Space magazine, March 1999

- Secret A-12 Spy Plane Officially Unveiled at CIA's Headquarters

- Project Oxcart: CIA Report

| ||

| ||

Go there...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lockheed_A-12

Lockheed YF-12

| YF-12 | |

|---|---|

| YF-12A undergoing flight testing. | |

| Role | Interceptor aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Corporation |

| Designer | Clarence "Kelly" Johnson |

| First flight | 7 August 1963 |

| Status | Canceled |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 3 |

| Unit cost | US$15–18 million (projected)[1] |

| Developed from | Lockheed A-12 |

The Lockheed YF-12 was an American prototype interceptor aircraft, which the United States Air Force evaluated as a development of the highly-secret Lockheed A-12 that also spawned the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird.

Contents |

Design and development

In the late 1950s the United States Air Force (USAF) sought a replacement for its F-106 Delta Dart interceptor. As part of the Long Range Interceptor Experimental (LRI,X) program, the North American XF-108 Rapier, an interceptor with Mach 3 speed, was selected. However, the F-108 program was canceled by the Department of Defense in September 1959.[2] During this time Lockheed's Skunk Works was developing the A-12 reconnaissance aircraft for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) under the Oxcart program. Kelly Johnson, the head of Skunk Works, proposed to build a version of the A-12 named AF-12 by the company; the USAF ordered three AF-12s in mid-1960.[3]

The AF-12s took the seventh through ninth slots on the A-12 assembly line; these were designated as YF-12A interceptors.[4] The main changes involved modifying the A-12's nose to accommodate the Hughes AN/ASG-18 fire-control radar originally developed for the XF-108, and the addition of the second cockpit for a crew member to operate the fire control radar for the air-to-air missile system. The modifications changed the aircraft's aerodynamics enough to require ventral fins to be mounted under the fuselage and engine nacelles to maintain stability. The four bays previously used to house the A-12's reconnaissance equipment were converted to carry Hughes AIM-47 Falcon (GAR-9) missiles.[5] One bay was used for fire control equipment.[6]

The first YF-12A flew on 7 August 1963.[5] President Lyndon B. Johnson announced the existence of the aircraft[7][8] on 24 February 1964.[9][10] The YF-12A was announced in part to continue hiding the A-12, its still-secret ancestor; any sightings of CIA/Air Force A-12s based at Area 51 in Nevada could be attributed to the well-publicized Air Force YF-12As based at Edwards Air Force Base in California.[8]

On 14 May 1965 the Air Force placed a production order for 93 F-12Bs for its Air Defense Command (ADC).[11] However, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara would not release the funding for three consecutive years due to Vietnam War costs.[11] Updated intelligence placed a lower priority on defense of the continental US, so the F-12B was deemed no longer needed. Then in January 1968, the F-12B program was officially ended.[12]

Operational history

Air Force testing

During flight tests the YF-12As set a speed record of 2,070.101 mph (3,331.505 km/h) and altitude record of 80,257.86 ft (24,462.6 m), both on 1 May 1965,[9] and demonstrated promising results with their unique weapon system. Six successful firings of the AIM-47 missiles were completed. The last one launched from the YF-12 at Mach 3.2 at an altitude of 74,000 ft (22,677 m) to a JQB-47E target drone 500 ft (152 m) off the ground.[13] One of the Air Force test pilots, Jim Irwin would go on to become a NASA astronaut and walk on the Moon.

The program was abandoned following the cancellation of the production F-12B, but the YF-12s continued flying for many years with the USAF and with NASA as research aircraft.

| This section requires expansion with: Fill in holes on USAF and NASA flight testing. (December 2009) |

NASA testing

The initial phase of this program included test objectives aimed at answering some questions about implementation of the B-1. Air Force objectives included exploration of its use in a tactical environment, and how AWACS would control supersonic aircraft. The Air Force portion was budgeted at US$4 million. The NASA tests would answer questions such as how engine inlet performance affected airframe and propulsion interaction, boundary layer noise, heat transfer under high Mach conditions, and altitude hold at supersonic speeds. The NASA budget for the 2.5-year program was US$14 million.[14]

Of the three YF-12As, #60-6934 was damaged beyond repair by fire at Edwards during a landing mishap on 14 August 1966; its rear half was salvaged and combined with the front half of a Lockheed static test airframe to create the only SR-71C.[15][16]

YF-12A #60-6936 was lost on 24 June 1971 due to an in-flight fire caused by a failed fuel line; both pilots ejected safely just north of Edwards AFB. YF-12A #60-06935 is the only surviving YF-12A; it was recalled from storage in 1969 for a joint USAF/NASA investigation of supersonic cruise technology, and then flown to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio on 17 November 1979.[9]

A fourth YF-12 aircraft, the "YF-12C", was actually the second SR-71A (61–7951). This SR-71A was re-designated as a YF-12C and given a fictitious serial number 60-6937 from an A-12 to maintain SR-71 secrecy. The YF-12C was loaned to NASA for propulsion testing after the loss of YF-12A (60–6936) in 1971. The YF-12C was operated by NASA until September 1978, when it was returned to the Air Force.[17]

The YF-12 had a real-field sonic-boom overpressure value between 33.5 to 52.7 N/m2 (0.7 to 1.1 lb/ft2) - below 48 was considered "low".[18]

Variants

- YF-12A

- Pre-production version. Three were built.[19]

- F-12B

- Production version of the YF-12A; canceled before production could begin.[20]

- YF-12C

- Fictitious designation for an SR-71 provided to NASA for flight testing. The YF-12 designation to keep SR-71 information out of the public domain.[21]

Operators

Specifications (YF-12A)

Data from Lockheed's SR-71 'Blackbird' Family[22]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 101 ft 8 in (30.97 m)

- Wingspan: 55 ft 7 in (16.95 m)

- Height: 18 ft 6 in (5.64 m)

- Wing area: 1,795 ft² (167 m²)

- Empty weight: 60,730 lb (27,604 kg)

- Loaded weight: 124,000 lb (56,200 kg[5])

- Max. takeoff weight: 140,000 lb (63,504 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney J58/JTD11D-20A high-bypass-ratio turbojet with afterburner (turbo/ramjet hybrid)

- Dry thrust: 20,500 lbf (91.2 kN) each

- Thrust with afterburner: 31,500 lbf (140 kN) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 3.35 (2,275 mph, 3,661 km/h[5]) at 80,000 ft (24,400 m)

- Range: 3,000 mi (4,800 km)

- Service ceiling: 90,000 ft (27,400 m)

Armament

- Missiles: 3× Hughes AIM-47A air-to-air missiles located internally in fuselage bays

Avionics

- Hughes AN/ASG-18 look-down/shoot-down fire control radar

Aircraft disposition

| Serial number | Model | Location or fate |

|---|---|---|

| 60-6934 | YF-12A | Transformed into SR-71C 61-7981 after fire damage in 1966, on display at Hill Aerospace Museum, Hill AFB, UT |

| 60-6935 | YF-12A | National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH |

| 60-6936 | YF-12A | Lost, 24 June 1971 |

The sole remaining YF-12A is located at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, near Dayton, Ohio.[9] This aircraft has small patches in its skin, on the starboard side below the cockpit. The patches cover holes caused by the "spurs" of a crewman who had to evacuate the plane after an emergency landing. The "YF-12C" (actually SR-71A, serial 61-7951) is on display at the Pima Air Museum in Tucson, AZ as of 2005.[17]

See also

- Related development

- Related lists

References

- Notes

- ^ Knaack, 1978.

- ^ Pace 2004, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Pace 2004, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d Green and Swanborough, 1988, p. 350.

- ^ Hughes AIM-47 Falcon

- ^ Johnson's speech named the plane A-11, the name for the two-seat design.

- ^ a b McIninch 1996, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Air Force Museum Foundation, 1983, p. 133.

- ^ McIninch 1996, p. 14.

- ^ a b Pace 2004, p. 53.

- ^ Donald 2003, pp. 148, 150.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Drendel 1982, p. 6.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 62, 75.

- ^ Pace 2004, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 49–55.

- ^ Dugan, James F. Jr. Preliminary study of supersonic-transport configurations with low values of sonic boom p18. NASA Lewis Research Center, March 1973. Accessed: March 2012.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, p. 46.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Goodall and Miller, 2002.

- Bibliography

- Air Force Museum Foundation Inc. US Air Force Museum. Dayton, Ohio: Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, 1983.

- Donald, David, ed. "Lockheed's Blackbirds: A-12, YF-12 and SR-71". Black Jets. AIRtime, 2003. ISBN 1-880588-67-6.

- Drendel, Lou. SR-71 Blackbird in Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1982, ISBN 0-89747-136-9.

- Goodall, James and Jay Miller. Lockheed's SR-71 'Blackbird' Family. Hinchley, England: Midland Publishing, 2002. ISBN 1-85780-138-5.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Complete Book of Fighters. New York: Barnes & Noble Inc., 1988. ISBN 0-7607-0904-1.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. Lockheed Secret Projects: Inside the Skunk Works. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7603-0914-8.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. and Tony R. Landis. Experimental & Prototype U.S. Air Force Jet Fighters. Minnesota, US:Specialty Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58007-111-6.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of US Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume 1 Post-World War II Fighters 1945–1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1978. ISBN 0-912799-59-5.

- Landis, Tony R. and Dennis R. Jenkins. Lockheed Blackbirds. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, revised edition, 2005. ISBN 1-58007-086-8.

- McIninch, Thomas. "THE OXCART STORY". Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 2 July 1996. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- Pace, Steve. Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird. Swindon: Crowood Press, 2004. ISBN 1-86126-697-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Lockheed YF-12 |

- Mach 3+: NASA/USAF YF-12 Flight Research, 1969–1979 by Peter W. Merlin (PDF book)

- YF-12A Flight Manual and YF-12A #60-6935 Photos on SR-71.org

- YF-12 fact sheet on USAF Museum site

- Blackbird Spotting maps the location of every existing Blackbird, with aerial photos from Google Maps

- USAF Aircraft Serial Numbers for 1960, including all A-12s, YF-12As, and M-21s

| ||

| ||

| ||

Go there...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lockheed_YF-12

Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird

| SR-71 "Blackbird" | |

|---|---|

| An SR-71B trainer over the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California in 1994. The raised second cockpit is for the instructor. | |

| Role | Strategic reconnaissance aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Skunk Works |

| Designer | Clarence "Kelly" Johnson |

| First flight | 22 December 1964 |

| Introduction | 1966 |

| Retired | 1998 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | United States Air Force NASA |

| Number built | 32 |

| Developed from | Lockheed A-12 |

The Lockheed SR-71 "Blackbird" was an advanced, long-range, Mach 3+ strategic reconnaissance aircraft.[1] It was developed as a black project from the Lockheed A-12 reconnaissance aircraft in the 1960s by the Lockheed Skunk Works. Clarence "Kelly" Johnson was responsible for many of the design's innovative concepts. During reconnaissance missions the SR-71 operated at high speeds and altitudes to allow it to outrace threats. If a surface-to-air missile launch was detected, the standard evasive action was simply to accelerate and outrun the missile.[2]

The SR-71 served with the U.S. Air Force from 1964 to 1998. Of the 32 aircraft built, 12 were destroyed in accidents, and none were lost to enemy action.[3][4] The SR-71 has been given several nicknames, including Blackbird and Habu, the latter in reference to an Okinawan species of pit viper.[5] Since 1976, it has held the world record for the fastest air-breathing manned aircraft, a record previously held by the YF-12.[6][7][8]

Contents |

Development

Background

Lockheed's previous reconnaissance aircraft was the U-2, which was designed for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In 1960, while overflying the USSR, the U-2 flown by Francis Gary Powers was shot down by Soviet surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). This highlighted the U-2's vulnerability due to its relatively low speed, and paved the way for the Lockheed A-12, also designed for the CIA by Kelly Johnson at Lockheed's Skunk Works.[9] The A-12 was the precursor of the SR-71. The A-12's first flight took place at Groom Lake (Area 51), Nevada, on 25 April 1962. It was equipped with the less powerful Pratt & Whitney J75 engines due to protracted development of the intended Pratt & Whitney J58. The J58s were retrofitted as they became available, and became the standard powerplant for all subsequent aircraft in the series (A-12, YF-12, M-21) as well as the follow-on SR-71 aircraft.

Thirteen A-12s were built. Two A-12 variants were also developed, including three YF-12A interceptor prototypes, and two M-21 drone carrier variants. The cancellation of A-12 program was announced on 28 December 1966,[10] due to budget concerns,[11] and because of the forthcoming SR-71. The A-12 flew missions over Vietnam and North Korea before its retirement in 1968.

SR-71

The SR-71 designator is a continuation of the pre-1962 bomber series, which ended with the XB-70 Valkyrie. During the later period of its testing, the B-70 was proposed for a reconnaissance/strike role, with an RS-70 designation. When it was clear that the A-12 performance potential was much greater, the Air Force ordered a variant of the A-12 in December 1962.[12] Originally named R-12[N 1] by Lockheed, the Air Force version was longer and heavier than the A-12, with a longer fuselage to hold more fuel, two seats in the cockpit, and reshaped chines. Reconnaissance equipment included signals intelligence sensors, a side-looking radar and a photo camera.[12] The CIA's A-12 was a better photo reconnaissance platform than the Air Force's R-12, since the A-12 flew somewhat higher and faster,[11] and with only one pilot it had room to carry a superior camera[11] and more instruments.[13]

During the 1964 campaign, Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater repeatedly criticized President Lyndon B. Johnson and his administration for falling behind the Soviet Union in developing new weapons. Johnson decided to counter this criticism by revealing the existence of the YF-12A Air Force interceptor, which also served as cover for the still-secret A-12,[14] and the Air Force reconnaissance model since July 1964. Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay preferred the SR (Strategic Reconnaissance) designation and wanted the RS-71 to be named SR-71. Before the July speech, LeMay lobbied to modify Johnson's speech to read SR-71 instead of RS-71. The media transcript given to the press at the time still had the earlier RS-71 designation in places, creating the story that the president had misread the aircraft's designation.[15][N 2]

Production of the SR-71 totaled 32 aircraft with 29 SR-71As, 2 SR-71Bs, and the single SR-71C.[16]

Design

The SR-71 was designed to minimize its radar cross-section, an early attempt at stealth design.[17]

The high temperatures generated by Mach 3 flight required its airframe to be made mostly of titanium. To control costs, Lockheed used a more easily worked alloy of titanium which softened at a lower temperature.[18]

Finished aircraft were painted a dark blue, almost black, to increase the emission of internal heat and to act as camouflage against the night sky. The dark color led to the aircraft's call sign "Blackbird".

Air inlets

The air inlets had to be designed to allow for cruising at over Mach 3.2, yet keep air flowing into the engines at the initial subsonic speeds. At the front of each inlet was a sharply-pointed movable cone called a "spike" that was locked in its full forward position on the ground and during subsonic flight. As the aircraft accelerated past Mach 1.6, an internal jackscrew withdrew the spike as much as 26 inches (66 cm) inwards;[19] an analogue air inlet computer, based on pitot-static, pitch, roll, yaw, and angle-of-attack inputs, would determine how much movement was required. By moving, the spike tip would withdraw the shock wave, riding on it closer to the inlet cowling until it just touched slightly inside the cowling lip. In this position shock-wave spillage, causing turbulence over the outer nacelle and wing, was minimized while the spike shock-wave repeatedly reflected between the spike centerbody and the inlet inner cowl sides. In doing so, shock pressures were maintained while slowing the air until a Mach 1 shock wave formed in front of the engine compressor.[20]

The backside of this "normal" shock wave was subsonic air for ingestion into the engine compressor. This capture of the Mach 1 shock wave within the inlet was called "Starting the Inlet". Tremendous pressures would be built up inside the inlet and in front of the compressor face. Bleed tubes and bypass doors were designed into the inlet and engine nacelles to handle some of this pressure and to position the final shock to allow the inlet to remain "started". Air that is compressed by the inlet/shockwave interaction is diverted directly into the afterburner to be mixed and burned. This configuration is essentially a ramjet and provides up to 70% of the aircraft's thrust at higher mach numbers.[citation needed] Ben Rich, the Skunkworks designer of the inlets, often referred to the engine compressors as "pumps to keep the inlets alive" and sized the inlets for Mach 3.2 cruise, the aircraft's most efficient speed.[21] The additional thrust refers to the reduction of engine power required to compress the airflow; the SR-71 was more fuel-efficient at higher speeds, in terms of pounds burned per nautical mile traveled. In one incident, SR-71 pilot Brian Shul conducted a mission where he had to maintain a higher than normal speed for some time in order to avoid multiple interception attempts; afterwards it was discovered that this had reduced their fuel consumption.[22]

In the early years of operation, the analog computers would not always keep up with rapidly changing flight environmental inputs. If internal pressures became too great and the spike was incorrectly positioned, the shock wave would suddenly blow out the front of the inlet, called an "Inlet Unstart." During an unstart, air flow through the engine compressor immediately stopped, thrust dropped, and exhaust gas temperatures rose. The remaining engine's asymmetrical thrust would cause the aircraft to yaw violently to one side during an unstart. SAS, autopilot, and manual control inputs would fight the yawing, but often the extreme off-angle would reduce airflow in the opposite engine and stimulate "sympathetic stalls". This generated a rapid counter-yawing, often coupled with loud "banging" noises and a rough ride, crews' helmets would sometimes strike their cockpit canopies until the violent motions subsided.[23] One practiced response to an inlet unstart was a pilot-commanded unstart of both inlets to prevent yawing, prior to the restart of both inlets.[24] Lockheed implemented an electronic control to detect unstart conditions and perform this reset action without pilot intervention.[25] Beginning in 1980, the analog inlet control system was replaced by a digital system, which prevented and reduced unstart instances.[26]

Airframe

On most aircraft, use of titanium was limited by the costs involved in procurement and manufacture. It was generally used only in components exposed to the highest temperatures, such as exhaust fairings and the leading edges of wings. On the SR-71, titanium was used for 85% of the structure, with the rest of composite materials. As such, the SR-71 was a ground-breaking aircraft, and some of the fabrication methods employed by Lockheed have since been used in the manufacture of many jet fighters and other aircraft. Titanium requires distilled water to be used during welding, because the chlorine in tap water causes corrosion; similarly, the cadmium-plated tools used on other aircraft were also found to cause corrosion, and had to be replaced.[27] Metallurgical contamination was another problem; at one point, it caused the rejection of 80% of the titanium delivered for the project.[28][29]

The high temperatures generated during flight required special design and operating techniques. For example, major portions of the skin of the inboard wings were corrugated, not smooth. (Aerodynamicists initially opposed the concept and accused the design engineers of trying to make a Mach-3 variant of the 1920s-era Ford Trimotor, known for its corrugated aluminum skin.[21]) The heat of flight would have caused a smooth skin to split or curl, but the corrugated skin could expand vertically and horizontally. The corrugation also increased longitudinal strength. Similarly, the fuselage panels were manufactured to fit only loosely on the ground. Proper alignment was only achieved when the airframe heated up and expanded several inches. Because of this, and the lack of a fuel sealing system that could handle the thermal expansion of the airframe at extreme temperatures, the aircraft would leak JP-7 jet fuel on the runway. At the beginning of each mission, the aircraft would make a short sprint after takeoff to warm up the airframe, then refuel before heading off to its destination.

Cooling was carried out by cycling fuel behind the titanium surfaces in the chines. On landing, the canopy temperature was over 300 °C (572 °F).[21]

Studies of the aircraft's titanium skin revealed that the metal was actually growing stronger over time, because of intense heating caused by compression of the air at high speeds acting as a regular heat treatment.[citation needed]

The red stripes on some SR-71s are to prevent maintenance workers from damaging the skin. The curved skin near the fuselage's center is thin and delicate; there is no support underneath except for the widely spaced structural ribs.[citation needed] Non-fibrous asbestos with high heat tolerance was used in high-temperature areas.[citation needed]

Stealth and threat avoidance

The SR-71 was the first operational aircraft designed around a stealthy shape and materials. There were a number of features in the SR-71 that were designed to reduce its radar signature. The first studies in radar stealth technology seemed to indicate that a shape with flattened, tapering sides would reflect most radar energy away from the radar beams' place of origin. To this end, engineers suggested the addition of chines and an inward canting of the vertical control surfaces. Special radar-absorbing materials were incorporated into sawtooth shaped sections of the aircraft's skin, as well as cesium-based fuel additives to reduce the visibility of exhaust plumes to radar. However, the SR-71 was still easily detected on radar while traveling at speed due to its large high-temperature exhaust stream. The SR-71 had a radar cross section (RCS) of around 10 square meters,[30] much greater than the later Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk, which had an RCS equivalent in size to a ball bearing.[31]

Rich's team showed that the radar return was reduced, Kelly Johnson later conceded that Russian radar technology advanced faster than the "anti-radar" technology employed against it.[32] Although equipped with a suite of electronic countermeasures, the SR-71's greatest protection was its top speed, making it almost invulnerable to the era's weapons technologies. In its service life, no SR-71 was shot down, despite attempts to do so. It flew too fast and too high for surface-to-air missile systems and was faster than the Soviet Union's principal interceptor, the MiG-25.[33] Accelerating would typically be enough to evade a missile fired against an SR-71.[2]

Chines

The SR-71 featured chines, a pair of sharp edges leading aft from either side of the nose along the fuselage. These were not a feature on the early A-3 design; Dr. Frank Rodgers, of the Scientific Engineering Institute (a CIA front company), had discovered that a cross-section of a sphere had a greatly reduced radar reflection, and adapted a cylindrical-shaped fuselage by stretching out the sides of the fuselage.[34] After the advisory panel provisionally selected Convair's FISH design over the A-3 on the basis of RCS, Lockheed adopted chines for its A-4 through A-6 designs.[35] When the Blackbird was being designed, no other airplane had featured chines, and Lockheed's engineers had to solve problems related to the differences in stability and balance caused by these unusual surfaces.[citation needed] Chines remain an important design feature of many of the newest stealth UAVs, such as the Dark Star, Bird of Prey, X-45 and X-47, since they allow for tail-less stability as well as for stealth.[citation needed]

Aerodynamicists discovered that the chines generated powerful vortices and created additional lift, leading to unexpected aerodynamic performance improvements.[36] The angle of incidence of the delta wings could then be reduced for greater stability and less drag at high speeds; more weight, such as fuel, could be carried to increase range. Landing speeds were also reduced, since the chines' vortices created turbulent flow over the wings at high angles of attack, making it harder for the wings to stall. High-alpha turns were limited by the capability of the engine inlets to ingest air, possibly resulting in flame out.[37] Pilots were thus warned not to pull more than 3 g and to avoid high angles of attack. The chines also acted like the leading edge extensions that increase the agility of modern fighters such as the F-5, F-16, F/A-18, MiG-29 and Su-27. The addition of chines also enabled the removal of the planned canard foreplanes.[N 3][38][39]

Fuel

Several exotic fuels were investigated for the Blackbird. Development began on a coal slurry powerplant, but Johnson determined that the coal particles damaged important engine components.[21] Research was conducted on a liquid hydrogen powerplant, however the tanks for storing cryogenic hydrogen were not of a suitable size or shape.[21] In practice, the Blackbird would burn somewhat conventional JP-7 jet fuel, however it was an unusual mixture composed primarily of hydrocarbons, also included alkanes, cycloalkanes, alkylbenzenes, indanes/tetralins, and naphthalenes.[citation needed] Fluorocarbons were present to increase its lubricity, an oxidizing agent to enable it to burn in the engines, and a cesium compound, A-50, to disguise the exhaust's radar signature.[citation needed]

The aircraft was prone to minor fuel leaks while on the ground. While slippery, it was not an urgent fire hazard as JP-7 had a relatively high flash point (140 °F, 60 °C). This also allowed its use as a coolant and hydraulic fluid in the SR-71.[citation needed] JP-7 was extremely difficult to light. To start the engines, triethylborane (TEB), which ignites on contact with air, was injected to produce temperatures high enough to ignite the JP-7. The TEB produced a characteristic green flame that can often be seen during engine ignition.[22] TEB was also used to ignite the afterburners. The aircraft carried 20 fluid ounces (600 ml) of TEB per engine, enough for at least 16 injections.[citation needed]

Life support

The cabin could be pressurized to an altitude of 10,000 ft (3,000 m) or 26,000 ft (7,900 m) during flight.[40] Crews flying a low-subsonic flight (such as a ferry mission) could wear standard USAF hard-hat helmets, pressure demand oxygen masks and Nomex flying suits.[citation needed]

But crews flying at 80,000 ft (24,000 m) could not use standard masks, which could not provide enough oxygen above 43,000 ft (13,000 m); moreover, the difference in air pressure between the cockpit and the space inside the mask would make exhalation extremely difficult. Furthermore, an emergency ejection at Mach 3.2 would subject crews to an instant heat rise of about 450 °F (230 °C).

To solve these problems, the David Clark Company produced protective pressurised suits for the A-12, YF-12, M-21 and SR-71 aircraft. Similar suits were used on the Space Shuttle.[citation needed] If a crew member had to bail out at high altitude, his suit's onboard oxygen supply would keep it pressurized. The crew member would freefall, allowing heat to bleed off, until the main parachute was opened at 15,000 ft (4,600 m). To test the suits, crew members would undergo explosive decompression in an altitude chamber at 78,000 ft (24,000 m) or higher while heaters would be turned on to 450 °F (230 °C), gradually decreasing at the expected rate in free-fall.[citation needed]

The cabin itself needed a heavy-duty cooling system, for cruising at Mach 3.2 would heat the aircraft's external surface well beyond 500 °F (260 °C)[41] and the inside of the windshield to 250 °F (120 °C). An air conditioner used a heat exchanger to dump heat from the cockpit into the fuel prior to the combustion.[citation needed]

Engines

The Blackbird's Pratt & Whitney J58-P4 engines were innovative marvels that used the most extreme materials of their time. Each J58 could produce 32,500 lbf (145 kN) of static thrust.[42] The only American engines designed to operate continuously on afterburner, the J58 engines were most efficient around Mach 3.2,[43][44] and this was the Blackbird's typical cruising speed.

A unique hybrid, the engine can be thought of as a turbojet inside a ramjet. At lower speeds, the turbojet provided most of the compression and most of the energy from fuel combustion. At higher speeds, the turbojet largely ceased to provide thrust; instead, air was compressed by the shock cones and fuel burned in the afterburner.

In detail, air was initially compressed (and thus also heated) by the shock cones, which generated shock waves that slowed the air down to subsonic speeds relative to the engine. The air then passed through four compressor stages and was split by movable vanes: some of the air entered the compressor fans ("core-flow" air), while the rest of the air went straight to the afterburner (via six bypass tubes). The air traveling through the turbojet was further compressed (and further heated), and then fuel was added to it in the combustion chamber: it then reached the maximum temperature anywhere in the Blackbird, just low enough to keep the turbine blades from softening. After passing through the turbine (and thus being cooled somewhat), the core-flow air went through the afterburner and met with any bypass air.

Around Mach 3, the increased heating from the shock cone compression, plus the heating from the compressor fans, was enough to get the core air to high temperatures, and little fuel could be added in the combustion chamber without melting the turbine blades. This meant the whole compressor-combustor-turbine set-up in the core of the engine provided less power, and the Blackbird flew predominantly on air bypassed straight to the afterburners, forming a large ramjet effect.[21][45][46] The maximum speed was limited by the specific maximum temperature for the compressor inlet of 800 °F (427 °C).

Early 1990s studies of inlets of this type indicated that newer technology could allow for inlet speeds with a lower limit of Mach 6.[47]

Startup

Originally, the Blackbird's engines started up with the assistance of an external engine referred to as a "start cart". The cart included two Buick Wildcat V8 engines positioned underneath the aircraft. The two engines powered a single, vertical driveshaft connecting to a single J58 engine. Once one engine was started, the cart was wheeled to the other side of the aircraft to start the other engine. The operation was deafening. Later, big-block Chevrolet engines were used. Eventually, a quieter, pneumatic start system was developed for use at Blackbird main operating bases, but the start carts remained to support recovery team Blackbird starts at diversion landing sites not equipped to start J-58 engines.[48]

Prior to the advent of the Global Positioning System (GPS) for navigation, the SR-71 required a precision navigation system for maintaining route accuracy and target tracking at very high speeds. Inertial navigation systems had been employed by the U-2 and A-12, but USAF planners wanted a system not vulnerable to inertial position error accumulation that would limit mission lengths.[citation needed] An astro-inertial navigation system (ANS) was devised that could correct inertial orientation errors with celestial observations. Nortronics, Northrop's electronics development organization, had in the mid-1950s developed an ANS for the SM-62 Snark missile and a separate system for the AGM-48 Skybolt missile. Following Skybolt's cancellation in December 1962, work began on adapting this system for the SR-71's use.[citation needed]

The ANS was located behind the Reconnaissance Systems Officer (RSO)'s position, tracking stars through a circular window set in the upper fuselage.[22] A time-consuming primary alignment was performed on the ground to bring the inertial components to a high degree of accuracy prior to takeoff. In flight, a "blue light" source star tracker, able to see stars during day and night time, would continuously track a variety of stars as the aircraft's changing position brought them into view. The system's digital computer ephemeris contained data on 56 (later 61) stars.[49] The ANS could supply attitude and position inputs to flight controls and other systems, including the Mission Data Recorder, Auto-Nav steering to preset destination points, automatic pointing and control of cameras and sensors, and optical or SLR sighting of fix points loaded into the ANS before takeoff.[50]

Sensors and payloads

The SR-71 originally included optical/infrared imagery systems; side-looking airborne radar (SLAR); electronic intelligence (ELINT) gathering systems; defensive systems for countering missile and airborne fighters; and recorders for SLAR, ELINT and maintenance data.[citation needed] The SR-71 carried a Fairchild tracking camera and an HRB Singer infrared camera, both of which ran during the entire mission for route documentation, to respond to any accusations of overflight.[citation needed]

Because the SR-71 carried an observer behind the pilot, it could not use the A-12's principal sensor, a single large-focal-length optical camera that sat in the "Q-Bay" behind the cockpit. Instead, camera systems could be located either in the wing chines or the aircraft's interchangeable nose. Wide-area imaging was provided by two of Itek's Operational Objective Cameras (OOCs), which provided stereo imagery across the width of the flight track, or an Itek Optical Bar Camera (OBC), which gave continuous horizon-to horizon coverage. A closer view of the target area was given by the HYCON Technical Objective Camera (TEOC), that could be directed up to 45 degrees left or right of the centerline.[51] Initially, the TEOCs could not match the resolution of the A-12's larger camera, but rapidly-made improvements in both the camera and film improved this performance.[51][52]

Side-looking radar, built by Goodyear Aerospace, could be carried in the removable nose. In later life the radar was replaced by Loral's Advanced Synthetic Aperture Radar System (ASARS-1). Both the first SLR and ASARS-1 were ground mapping imaging systems, collecting data either in fixed swaths left or right of centerline or from a spot location for higher resolution.[51] ELINT-gathering systems, called the Electro Magnetic Reconnaissance System (EMR), built by AIL could be carried in the chine bays to analyse electronic signal fields being passed through, and were pre-programmed to identify items of interest.[51][53]

Over its operational life, the Blackbird carried various electronic countermeasures, including warning and active electronic systems built by several ECM companies and called Systems A, A2, A2C, B, C, C2, E, G, H and M. On a given mission, an aircraft would carry several of these frequency/purpose payloads to meet the expected threats.[citation needed] After landing, recording systems and gathered information from the SLR and ELINT systems, and the Maintenance Data Recorder (MDR) were subjected to post-flight ground analysis. In the later years of its operational life, a data-link system could send ASARS-1 and ELINT data from about 2,000 nmi (3,700 km) of track coverage to a suitably equipped ground station.[citation needed]

Operational history

The first flight of an SR-71 took place on 22 December 1964, at Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale, California.[54] The first SR-71 to enter service was delivered to the 4200th (later, 9th) Strategic Reconnaissance Wing at Beale Air Force Base, California, in January 1966.[55] The United States Air Force Strategic Air Command had SR-71 Blackbirds in service from 1966 through 1991.

SR-71s first arrived at the 9th SRW's Operating Location (OL-8) at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa on 8 March 1968.[56] These deployments were code named "Glowing Heat", while the program as a whole was code named "Senior Crown". Reconnaissance missions over North Vietnam were code named "Giant Scale".

On 21 March 1968, Major (later General) Jerome F. O'Malley and Major Edward D. Payne flew the first operational SR-71 sortie in SR-71 serial number 61-7976 from Kadena AB, Okinawa.[56] During its career, this aircraft (976) accumulated 2,981 flying hours and flew 942 total sorties (more than any other SR-71), including 257 operational missions, from Beale AFB; Palmdale, California; Kadena Air Base, Okinawa, Japan; and RAF Mildenhall, England. The aircraft was flown to the National Museum of the United States Air Force near Dayton, Ohio in March 1990.

From the beginning of the Blackbird's reconnaissance missions over enemy territory (North Vietnam, Laos, etc.) in 1968, the SR-71s averaged approximately one sortie a week for nearly two years. By 1970, the SR-71s were averaging two sorties per week, and by 1972, they were flying nearly one sortie every day.

While deployed in Okinawa, the SR-71s and their aircrew members gained the nickname Habu (as did the A-12s preceding them) after a pit viper indigenous to Japan, which the Okinawans thought the plane resembled.[5]

Swedish JA 37 Viggen fighter pilots, using the predictable patterns of SR-71 routine flights over the Baltic Sea, managed to lock their radar on the SR-71 on numerous occasions. Despite heavy jamming from the SR-71, target illumination was maintained by feeding target location from ground-based radars to the fire-control computer in the Viggen.[57] The most common site for the lock-on to occur was the thin stretch of international airspace between Öland and Gotland that the SR-71 used on the return flight.[58][59][60]

Operational highlights for the entire Blackbird family (YF-12, A-12, and SR-71) as of about 1990 included:[61]

- 3,551 Mission Sorties Flown

- 17,300 Total Sorties Flown

- 11,008 Mission Flight Hours

- 53,490 Total Flight Hours

- 2,752 hours Mach 3 Time (Missions)

- 11,675 hours Mach 3 Time (Total)

Only one crew member, Jim Zwayer, a Lockheed flight-test reconnaissance and navigation systems specialist, was killed in a flight accident. The rest of the crew members ejected safely or evacuated their aircraft on the ground.

The highly specialized tooling used to manufacture the SR-71 was ordered destroyed in 1968 by then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, per contractual obligations at the end of production.[citation needed] Destroying the tooling killed any chance of there being an F-12B and also limited the SR-71 force to the 32 completed, the final SR-71 order having to be cancelled when the tooling was destroyed.

First retirement

In the 1970s, the SR-71 was placed under closer congressional scrutiny and, with budget concerns, the program was soon under attack. Both Congress and the USAF sought to focus on newer projects like the B-1 Lancer and upgrades to the B-52 Stratofortress, whose replacement was being developed. While the development and construction of reconnaissance satellites was costly, their upkeep was less than that of the nine SR-71s then in service.[citation needed]

The SR-71 had never gathered significant supporters within the Air Force, making it an easy target for cost-conscious politicians. Also, parts were no longer being manufactured for the aircraft, so other airframes had to be cannibalized to keep the fleet airworthy. The aircraft's lack of a datalink (unlike the Lockheed U-2) meant that imagery and radar data could not be used in real time, but had to wait until the aircraft returned to base. The Air Force saw the SR-71 as a bargaining chip which could be sacrificed to ensure the survival of other priorities. A general misunderstanding of the nature of aerial reconnaissance and a lack of knowledge about the SR-71 in particular (due to its secretive development and usage) was used by detractors to discredit the aircraft, with the assurance given that a replacement was under development. In 1988, Congress was convinced to allocate $160,000 to keep six SR-71s (along with a trainer model) in flyable storage that would allow the fleet to become airborne within 60 days. The USAF refused to spend the money. While the SR-71 survived attempts to be retired in 1988, partly due to the unmatched ability to provide high quality coverage of the Kola Peninsula for the US Navy,[62] the decision to retire the SR-71 from active duty came in 1989, with the SR-71 flying its last missions in October that year.[63]

Funds were redirected to the financially troubled B-1 Lancer and B-2 Spirit programs. Four months after the plane's retirement, General Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr., was told that the expedited reconnaissance which the SR-71 could have provided was unavailable during Operation Desert Storm.[64] However, it was noted by SR-71 supporters that the SR-71B trainer was just coming out of overhaul and that one SR-71 could have been made available in a few weeks, and a second one within two months. Since the aircraft was recently retired, the support infrastructure was in place and qualified crews available. The decision was made by Washington not to bring the aircraft back.[citation needed]

Reactivation

Due to increasing unease about political conditions in the Middle East and North Korea, the U.S. Congress re-examined the SR-71 beginning in 1993.[64] At a hearing of the Senate Committee on Armed Services, Senator J. James Exon asked Admiral Richard C. Macke:

| “ | If we have the satellite intelligence that you collectively would like us to have, would that type of system eliminate the need for an SR-71… Or even if we had this blanket up there that you would like in satellites, do we still need an SR-71? | ” |

Macke replied,

| “ | From the operator's perspective, what I need is something that will not give me just a spot in time but will give me a track of what is happening. When we are trying to find out if the Serbs are taking arms, moving tanks or artillery into Bosnia, we can get a picture of them stacked up on the Serbian side of the bridge. We do not know whether they then went on to move across that bridge. We need the [data] that a tactical, an SR-71, a U-2, or an unmanned vehicle of some sort, will give us, in addition to, not in replacement of, the ability of the satellites to go around and check not only that spot but a lot of other spots around the world for us. It is the integration of strategic and tactical."[65] | ” |

Rear Admiral Thomas F. Hall addressed the question of why the SR-71 was retired, saying it was under "the belief that, given the time delay associated with mounting a mission, conducting a reconnaissance, retrieving the data, processing it, and getting it out to a field commander, that you had a problem in timeliness that was not going to meet the tactical requirements on the modern battlefield. And the determination was that if one could take advantage of technology and develop a system that could get that data back real time… that would be able to meet the unique requirements of the tactical commander." Hall stated that "the Advanced Airborne Reconnaissance System, which was going to be an unmanned UAV" would meet the requirements but was not affordable at the time. He said that they were "looking at alternative means of doing [the job of the SR-71]."[65]

Macke told the committee that they were "flying U-2s, RC-135s, [and] other strategic and tactical assets" to collect information in some areas.[65]

Senator Robert Byrd and other Senators complained that the "better than" successor to the SR-71 had yet to be developed at the cost of the "good enough" serviceable aircraft. They maintained that, in a time of constrained military budgets, designing, building, and testing an aircraft with the same capabilities as the SR-71 would be impossible.[61]

Congress' disappointment with the lack of a suitable replacement for the Blackbird was cited concerning whether to continue funding imaging sensors on the U-2. Congressional conferees stated the "experience with the SR-71 serves as a reminder of the pitfalls of failing to keep existing systems up-to-date and capable in the hope of acquiring other capabilities."[61]

It was agreed to add $100 million to the budget to return three SR-71s to service, but it was emphasized that this "would not prejudice support for long-endurance UAVs [such as the Global Hawk]." The funding was later cut to $72.5 million.[61] The Skunk Works was able to return the aircraft to service under budget, coming in at $72 million.[66]

Colonel Jay Murphy (USAF Retired) was made the Program Manager for Lockheed's reactivation plans. Retired Air Force Colonels Don Emmons and Barry MacKean were put under government contract to remake the plane's logistic and support structure. Still-active Air Force pilots and Reconnaissance Systems Officers (RSOs) who had worked with the aircraft were asked to volunteer to fly the reactivated planes. The aircraft was under the command and control of the 9th Reconnaissance Wing at Beale Air Force Base and flew out of a renovated hangar at Edwards Air Force Base. Modifications were made to provide a data-link with "near real-time" transmission of the Advanced Synthetic Aperture Radar's imagery to sites on the ground.[61]

Second retirement

The reactivation met much resistance: the Air Force had not budgeted for the aircraft, and UAV developers worried that their programs would suffer if money was shifted to support the SR-71s. Also, with the allocation requiring yearly reaffirmation by Congress, long-term planning for the SR-71 was difficult.[61] In 1996, the Air Force claimed that specific funding had not been authorized, and moved to ground the program. Congress reauthorized the funds, but, in October 1997, President Bill Clinton used the line-item veto to cancel the $39 million allocated for the SR-71. In June 1998, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the line-item veto was unconstitutional. All this left the SR-71's status uncertain until September 1998, when the Air Force called for the funds to be redistributed. The plane was permanently retired in 1998. The Air Force quickly disposed of their SR-71s, leaving NASA with the two last flyable Blackbirds until 1999.[67] All other Blackbirds have been moved to museums except for the two SR-71s and a few D-21 drones retained by the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center.[66]

SR-71 timeline

Important dates pulled from many sources.[68][unreliable source?]

- 24 December 1957: First J58 engine run.

- 1 May 1960: Francis Gary Powers is shot down in a Lockheed U-2 over the Soviet Union.

- 13 June 1962: SR-71 mock-up reviewed by Air Force.

- 30 July 1962: J58 completes pre-flight testing.

- 28 December 1962: Lockheed signs contract to build six SR-71 aircraft.

- 25 July 1964: President Johnson makes public announcement of SR-71.

- 29 October 1964: SR-71 prototype (#61-7950) delivered to Palmdale.

- 7 December 1964: Beale AFB, CA announced as base for SR-71.

- 22 December 1964: First flight of the SR-71 with Lockheed test pilot Bob Gilliland at AF Plant #42.

- 21 July 1967: Jim Watkins and Dave Dempster fly first international sortie in SR-71A #61-7972 when the Astro-Inertial Navigation System (ANS) fails on a training mission and they accidentally fly into Mexican airspace.

- 3 November 1967: A-12 and SR-71 conduct a reconnaissance fly-off. Results were questionable.

- 5 February 1968: Lockheed ordered to destroy A-12, YF-12, and SR-71 tooling.

- 8 March 1968: First SR-71A (#61-7978) arrives at Kadena AB to replace A-12s.

- 21 March 1968: First SR-71 (#61-7976) operational mission flown from Kadena AB over Vietnam.

- 29 May 1968: CMSgt Bill Gornik begins the tie-cutting tradition of Habu crews neck-ties.

- 3 December 1975: First flight of SR-71A #61-7959 in "Big Tail" configuration.

- 20 April 1976: TDY operations started at RAF Mildenhall in SR-71A #17972.

- 27–28 July 1976 : SR-71A sets speed and altitude records (Altitude in Horizontal Flight: 85,068.997 ft (25,929.030 m) and Speed Over a Straight Course: 2,193.167 miles per hour (3,529.560 km/h)).

- August 1980: Honeywell starts conversion of AFICS to DAFICS.

- 15 January 1982: SR-71B #61-7956 flies its 1,000th sortie.

- 21 April 1989: #974 was lost due to an engine explosion after taking off from Kadena AB. This was the last Blackbird to be lost, and was the first SR-71 accident in 17 years.[3][4]

- 22 November 1989: Air Force SR-71 program officially terminated.

- 21 January 1990: Last SR-71 (#61-7962) left Kadena AB.

- 26 January 1990: SR-71 is decommissioned at Beale AFB, CA.

- 6 March 1990: Last SR-71 flight under SENIOR CROWN program, setting four speed records enroute to Smithsonian Institution.

- 25 July 1991: SR-71B #61-7956/NASA #831 officially delivered to NASA Dryden.

- October 1991: Marta Bohn-Meyer becomes first female SR-71 crew member.

- 28 September 1994: Congress votes to allocate $100 million for reactivation of three SR-71s.

- 26 April 1995: First reactivated SR-71A (#61-7971) makes its first flight after restoration by Lockheed.

- 28 June 1995: First reactivated SR-71 returns to Air Force as Detachment 2.

- 28 August 1995: Second reactivated SR-71A (#61-7967) makes first flight after restoration.

- 2 August 1997: A NASA SR-71 made multiple flybys at the EAA AirVenture Oshkosh air show. It was then supposed to perform a sonic boom at 53,000 feet (16,000 m) after a midair refueling, but a fuel flow problem caused it to divert to Milwaukee. Two weeks later, the pilot's flight path brought him over Oshkosh again, and there was, in fact, a sonic boom.

- 19 October 1997: The last flight of SR-71B #61-7956 at Edwards AFB Open House.

- 9 October 1999: The last flight of the SR-71 (#61-7980/NASA 844).

- September 2002: Final resting places of #956, #971, and #980 are made known.[69]

- 15 December 2003: SR-71 #972 goes on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

Records

The SR-71 was the world's fastest and highest-flying operational manned aircraft throughout its career. On 28 July 1976, SR-71 serial number 61-7962 broke the world record for its class: an "absolute altitude record" of 85,069 feet (25,929 m).[8][70][71][72] Several aircraft exceeded this altitude in zoom climbs but not in sustained flight.[8] That same day SR-71, serial number 61-7958 set an absolute speed record of 1,905.81 knots (2,193.2 mph; 3,529.6 km/h).[8][72]

The SR-71 also holds the "Speed Over a Recognized Course" record for flying from New York to London distance 3,508 miles (5,646 km), 1,435.587 miles per hour (2,310.353 km/h), and an elapsed time of 1 hour 54 minutes and 56.4 seconds, set on 1 September 1974 while flown by U.S. Air Force Pilot Maj. James V. Sullivan and Maj. Noel F. Widdifield, reconnaissance systems officer (RSO).[73] This equates to an average velocity of about Mach 2.68, including deceleration for in-flight refueling. Peak speeds during this flight were probably closer to the declassified top speed of Mach 3.2+. For comparison, the best commercial Concorde flight time was 2 hours 52 minutes, and the Boeing 747 averages 6 hours 15 minutes.

On 26 April 1971, 61-7968 flown by Majors Thomas B. Estes and Dewain C. Vick flew over 15,000 miles (24,000 km) in 10 hrs. 30 min. This flight was awarded the 1971 Mackay Trophy for the "most meritorious flight of the year" and the 1972 Harmon Trophy for "most outstanding international achievement in the art/science of aeronautics".[74]

When the SR-71 was retired in 1990, one Blackbird was flown from its birthplace at United States Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale, California, to go on exhibit at what is now the Smithsonian Institution's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. On 6 March 1990, Lt. Col. Raymond "Ed" E. Yielding and Lt. Col. Joseph "Jt" T. Vida piloted SR-71 S/N 61-7972 on its final Senior Crown flight and set four new speed records in the process.

- Los Angeles, CA to Washington, D.C., distance 2,299.7 miles (3,701.0 km), average speed 2,144.8 miles per hour (3,451.7 km/h), and an elapsed time of 64 minutes 20 seconds.[73]

- West Coast to East Coast, distance 2,404 miles (3,869 km), average speed 2,124.5 miles per hour (3,419.1 km/h), and an elapsed time of 67 minutes 54 seconds.

- Kansas City, Missouri to Washington D.C., distance 942 miles (1,516 km), average speed 2,176 miles per hour (3,502 km/h), and an elapsed time of 25 minutes 59 seconds.

- St. Louis, Missouri to Cincinnati, Ohio, distance 311.4 miles (501.1 km), average speed 2,189.9 miles per hour (3,524.3 km/h), and an elapsed time of 8 minutes 32 seconds.

These four speed records were accepted by the National Aeronautic Association (NAA), the recognized body for aviation records in the United States.[75] After the Los Angeles–Washington flight, Senator John Glenn addressed the United States Senate, chastening the Department of Defense for not using the SR-71 to its full potential:

| “ | Mr. President, the termination of the SR-71 was a grave mistake and could place our nation at a serious disadvantage in the event of a future crisis. Yesterday's historic transcontinental flight was a sad memorial to our short-sighted policy in strategic aerial reconnaissance. | ” |

| —Senator John Glenn, 7 March 1990[76] | ||

Succession

Much speculation exists regarding a replacement for the SR-71, most notably aircraft identified as the Aurora. This is due to limitations of spy satellites, which are governed by the laws of orbital mechanics. It may take up to 24 hours before a satellite is in proper orbit to photograph a particular target, far longer than a reconnaissance plane. Spy planes can provide the most current intelligence information and collect it when lighting conditions are optimum. The fly-over orbit of spy satellites may also be predicted and can allow the enemy to hide assets when they know the satellite is above, a drawback spy planes do not exhibit. These factors have led many to doubt that the US has abandoned the concept of spy planes to complement reconnaissance satellites.[77] Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are also used for much aerial reconnaissance in the 2000s. They have the advantage of being able to overfly hostile territory without putting human pilots at risk.

Variants

- SR-71A was the main production variant.

- SR-71B was a trainer variant.[78]

- SR-71C was a hybrid aircraft composed of the rear fuselage of the first YF-12A (S/N 60-6934) and the forward fuselage from a SR-71 static test unit. The YF-12 had been wrecked in a 1966 landing accident. This Blackbird was seemingly not quite straight and had a yaw at supersonic speeds.[79] It was nicknamed "The Bastard".[80][81]

Specifications (SR-71A)

Data from SR-71.org,[82] Pace[83]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Payload: 3,500 lb (1,600 kg) of sensors

- Length: 107 ft 5 in (32.74 m)